Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is a language that gave rise to many others. About 46% of humans, well over three billion people, are native speakers of an Indo-European language. But where did PIE first arise, and who spoke it: pastoralists from the Pontic steppe straddling eastern Europe and west Asia or agrarians from Anatolia in Turkey? The answer to that question has been eluding anthropologists for ages. And now, researchers in the journal Science suggest a third place: the Lesser Caucasus, primarily found in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and parts of eastern Turkey and southern Georgia.

PIE is both the deadest and most alive of languages. The last speaker died thousands of years ago, and if it was ever written down, we don’t know about it. The only evidence of PIE’s existence are the traces it left in the languages that descended from it.

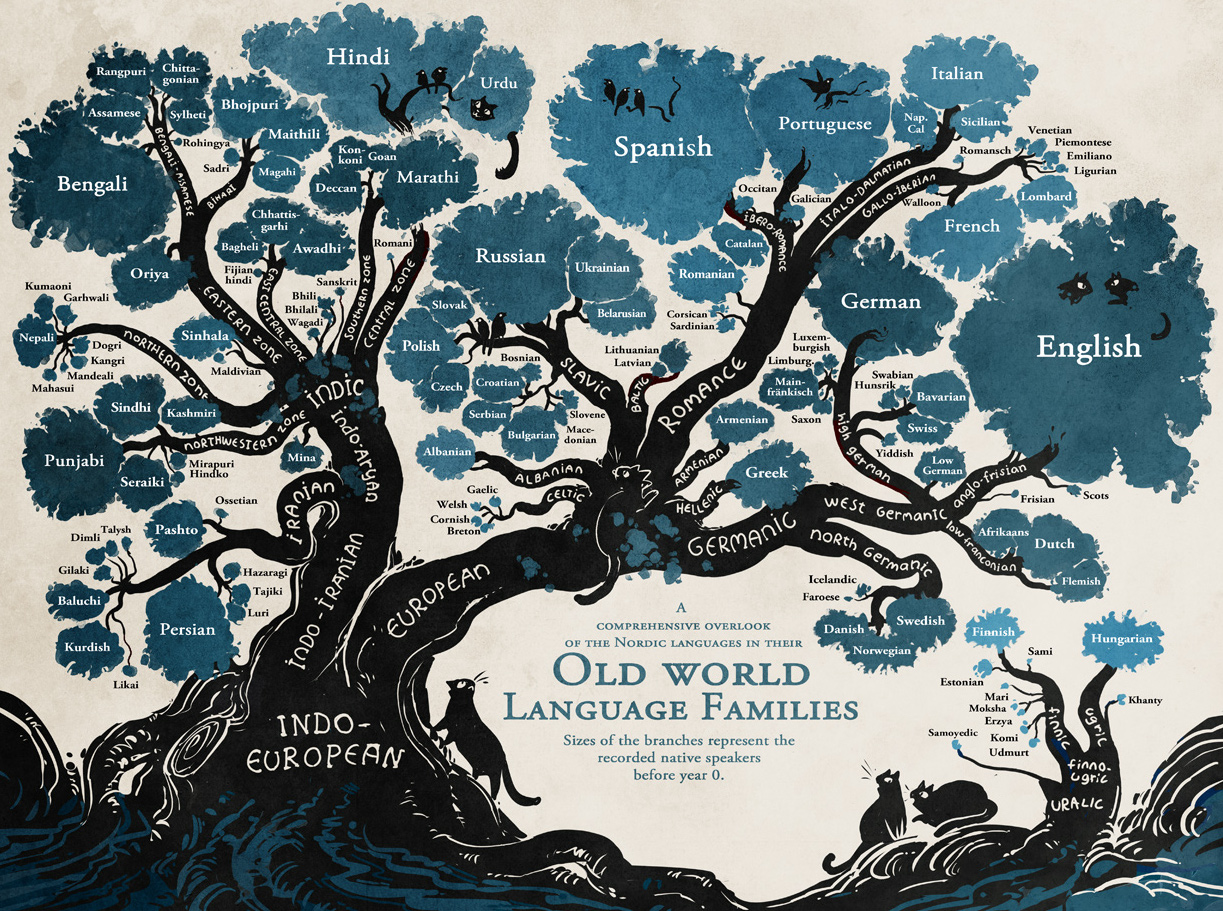

We say “only,” but that is a lot of evidence. Modern descendants of PIE include not only English, Spanish, and Russian, but also Persian, Hindi, Bengali, and dozens more. Indo-European is by far the largest language family in the world. Sino-Tibetan, which includes Mandarin Chinese, is a distant second, with about 1.3 billion native speakers.

For the better part of a century, linguists have been looking for clues to the origin of Indo-European from within the languages themselves. Using phylogenetic analysis — phylogenetics is the study of evolutionary relationships over time, be they organisms or languages — they have reconstructed a vocabulary for PIE that gives us an idea of the culture of the people who spoke it. We know they had words for bear (bʰérōs) and goose (h₂énos), willow (wélə) and honey (méli), and peat (péḱus) and enclosure (h₂órtos).

The language families descended from Proto-Indo-European beautifully rendered as the branches of a tree, with each leaf approximating the relative numbers of native speakers of each language. (Credit: Stand Still, Stay Silent by Minna Sundberg)

Based on such evidence, two schools of thought emerged. One proposed that PIE originated some 6,000 years ago in the Pontic-Caspian steppe located north of the Black and Caspian Seas, in the flatlands that stretch from northeast Romania via southern Ukraine and southwestern Russia into the furthest west of Kazakhstan. The nomadic pastoralists who lived here tamed the horse, allowing them to migrate far and wide. This is called the steppe or kurgan hypothesis, the latter after the local word for the prehistoric burial mounds that dot the area.

Other scholars posit an older and more southerly beginning for PIE: around 9,000 years ago in Anatolia. Also known as Asia Minor, this peninsula bordered by the Black, Aegean, and Mediterranean Seas is the westernmost extension of Asia. Today, it is the Asian part of Turkey. The theory is that the language piggybacked on the spread of agriculture from here to large parts of the Old World.

The kurgan hypothesis is the more widely accepted of the two. Many of its proponents think that PIE speakers, kurgan builders, and the ancient Yamnaya culture are actually one and the same. However, conflicting evidence from previous phylogenetic analyses has prevented either hypothesis from completely knocking out the other.

So, the Max Planck team constructed a new dataset of core vocabulary from 161 Indo-European languages that was more comprehensive and balanced than previous samples. Using recent advances in phylogenetic analysis, they were able to estimate that PIE was approximately 8,100 years old, and that five main branches had already split off around 7,000 years ago.

The study’s results fit poorly with both the kurgan and Anatolian hypotheses. As a solution, the researchers propose a third possibility: an early homeland for PIE immediately south of the Caucasus, with one migration veering off north into the steppe. There, PIE speakers established a “secondary homeland,” from where Indo-European entered the rest of Europe beginning 5,000 years ago, courtesy of the Yamnaya and later expansions.

Map showing the spread of Indo-European according to the kurgan hypothesis: from the Pontic steppe (dark green) to an area covering most of Europe and large parts of Asia (light green). Note the non-Indo-European language islands in Europe, representing Finnish, Estonian, Hungarian, and Basque. (Credit: Joe Roe, after Wolfgang Haak, CC BY-SA 4.0)

By offering a hybrid of the farming and pastoralist theories about the spread of Indo-European, the south-of-Caucasus hypothesis suggests a solution for an enigma that has dogged the study of Indo-European for about 200 years. Wolfgang Haak, group leader at the department of archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said:

“Aside from a refined time estimate for the overall language tree, the tree topology and branching order are most critical for the alignment with key archaeological events and shifting ancestry patterns seen in the ancient human genome data. This is a huge step forward from the mutually exclusive, previous scenarios, towards a more plausible model that integrates archaeological, anthropological, and genetic findings.”

Strange Maps #1220

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].