For months, the negotiations over the fate of Nagorno-Karabakh seemed to be going in Azerbaijan’s favor. Armenia’s government had publicly and explicitly said it recognized the breakaway territory — which is the center of the two countries’ decades-long conflict — as part of Azerbaijan. All that was to be worked out, in essence, were the details. So why did war break out again?

The Backdrop To War

At issue is Nagorno-Karabakh, a mountainous enclave of Azerbaijan that historically has been home to both Armenians and Azeris. On the eve of the collapse of the Soviet Union, the population of what was then the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast was roughly 75 percent ethnic Armenian. A nationalist movement in the 1980s sought to separate the territory from Azerbaijan and join it with Armenia. The ensuing war in the early 1990s killed some 30,000 people and resulted in Armenian-backed separatists seizing the territory from Azerbaijan.

Diplomatic efforts to settle the conflict brought little progress, and the two sides fought another war in 2020 that lasted six weeks before a Russian-brokered cease-fire effectively recognized the loss of Armenian control over parts of the region and seven adjacent districts.

In 2022, Baku and Yerevan embarked on negotiations aimed at finally resolving the conflict. Azerbaijan’s stated goal has been to regain full control over the rest of Karabakh, and Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinian has indicated that he was willing to comply.

But the Karabakh Armenian leadership has been more recalcitrant, fearing that Azerbaijani promises to peacefully “reintegrate” ethnic Armenians amounted to a smokescreen for a plan to eventually squeeze them out of the territory for good. International mediators had been trying to find a compromise to the standoff but with little to show for it.

So Why Did Azerbaijan Attack Now?

On September 19, Azerbaijan launched a wide-scale attack against Nagorno-Karabakh and the remnants of its armed forces, forcing residents of the region’s capital, Stepanakert (Xankendi in Azeri), to hunker down in bomb shelters and those in outlying settlements to evacuate to the center. After a day of attacks, the offensive achieved Baku’s stated aim: The de facto ethnic Armenian Karabakh authorities agreed to disband and disarm their armed forces.

The worst fears of violence now appear to be averted, with the Azerbaijani and ethnic Armenian sides agreeing on an immediate cease-fire. But the offensive laid bare how the dynamics of the conflict are all on Azerbaijan’s side, to the point where Baku felt that it was in its interest to accelerate the process with force, despite the possibility of facing international condemnation and risking the lives of the people in Nagorno-Karabakh it says are its citizens.

Azerbaijan has been dissatisfied with the pace of negotiations, complaining that the Karabakh Armenian leadership was digging in and becoming intransigent. Baku also may have seen a moment of opportunity when Armenia’s traditional security guarantor, Russia, had turned against the Armenian government and its leader, Pashinian. And finally, Azerbaijan likely calculated that whatever international costs it might face for the assault, they would not be too painful.

Was The Azerbaijani Offensive Unexpected?

The ostensible trigger for the operation was a mine explosion that killed six Azerbaijanis early in the morning on September 19, near the city of Xocavend, which is now under the control of Russian peacekeepers and a part of wider territory that Azerbaijani forces retook in the war in 2020. The Azerbaijani side blamed the mine attack on Armenian saboteurs from Karabakh.

But the preparations for the assault had been going on for weeks. Azerbaijani troops had massed on the line of contact separating Azerbaijani-controlled territory from the rump Karabakh entity that remained following the 2020 war. There were also reports of military cargo flights between Azerbaijan and Israel, suggesting that Azerbaijan may have been rearming in preparation for more fighting.

Baku’s rhetoric had also taken a notably sharper turn in recent weeks, as well. Azerbaijan “will not tolerate the presence of any gray zone in its territory,” Hikmet Haciyev, a senior adviser to Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev, said in late August. It was a reference to the part of Karabakh Azerbaijan did not yet control.

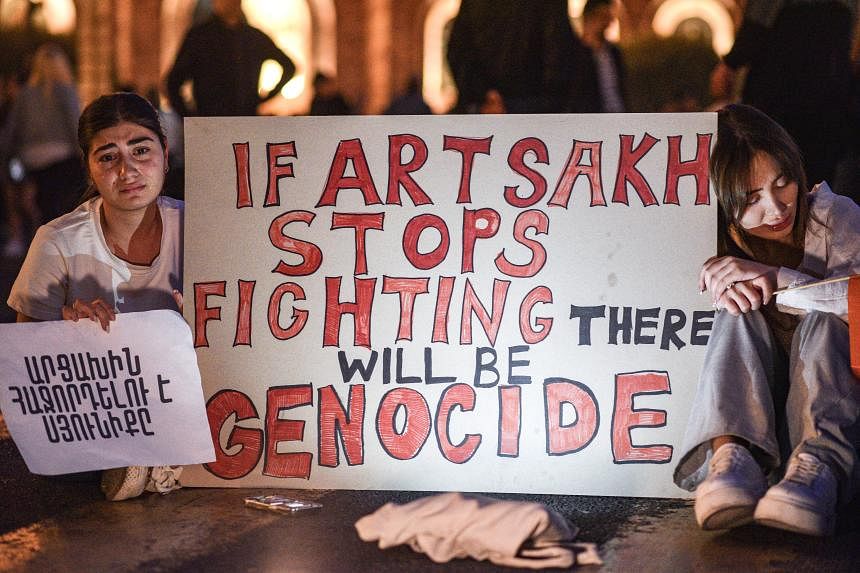

Photo Gallery:

Armenians took to the streets to demand Prime Minister Nikol Pashinian resign after Azerbaijan launched what it called an “anti-terrorist operation” targeting ethnic Armenian military positions in Nagorno-Karabakh that left at least 32 people dead and more than 200 wounded.

Well before this summer, analysts say that Azerbaijan had been using military escalations to push along the diplomatic process.

Talks between the central government in Baku and the Karabakh Armenians had stalled, with Azerbaijanis complaining about their interlocutors’ intransigence. “The Karabakh Armenians refused to talk about anything except independence,” said Farid Shafiyev, the head of the Azerbaijani government-run think tank Center of Analysis of International Relations. He noted that the de facto ethnic Armenian government had organized an election of a new president in early September 2022, a step that in Azerbaijani eyes confirmed the unwillingness to accept their rule.

But the Karabakh Armenian authorities’ position had been “evolving,” with a greater willingness to accede to Azerbaijan’s demands, said Olesya Vartanyan, the senior South Caucasus analyst at the Crisis Group think tank. “They were ready to meet in Azerbaijan and discuss the integration process — what Baku had been demanding.”

As the standoff dragged on, the risk of another attack from Azerbaijan rose. “The absence — or more accurately the stagnation — of the political process exacerbates these concerns,” Zaur Shiriyev, a Baku-based analyst for Crisis Group, said in an online discussion on September 15, just days before the offensive began. “If a military escalation occurs in the Armenian-populated areas of Karabakh in the coming days or weeks, it wouldn’t be a surprise.”

The Russia Factor

Accelerating the process was a rapid collapse in relations between Armenia and its traditional big-power patron, Russia. As part of the 2020 cease-fire agreement, a contingent of 2,000 Russian peacekeepers were deployed to the part of Karabakh that ethnic Armenians still controlled. But they have proven unable or unwilling to push back against steady Azerbaijani pressure on the territory. And Russia itself — despite having treaty obligations to defend Armenia in case of external attack, as both are members of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), a mutual defense pact — has not intervened in spite of repeated Azerbaijani incursions across the border into Armenia.

This led to an increasing estrangement between Yerevan and Moscow that came to a head this month, when the Armenian government took a series of seemingly calculated steps to signal its displeasure with Russia. Among them: It dispatched Pashinian’s wife, Anna Hakobian, to Kyiv to deliver a package of aid; it announced it intended to sign the treaty to join the International Criminal Court, which would in effect obligate it to arrest Russian President Vladimir Putin; and it withdrew its representative from the CSTO. “They crossed about three Russian red lines simultaneously,” said Thomas de Waal, an analyst at the think tank Carnegie Europe.

Baku appears to have been emboldened by the Russian-Armenian rift, says Shujaat Ahmadzada, a nonresident research fellow at the Baku-based Topchubashov Center, which focuses on international relations and security. “It points to Russia here more than other factors,” he said. “The only actor that could have caused problems to a degree [for Azerbaijan] was Russia, and now, given the Armenia-Russia decoupling, I think they believe the time is right.”

How Has The World Reacted?

As their position vis-a-vis Azerbaijan has weakened, and the alliance with Russia frayed, Armenia has been seeking international support wherever it can get it. It hosts border monitors from the European Union, is buying weapons from India, and regularly tries to bring up the conflict at the United Nations Security Council.

But it has thus far failed to get any international actor to take substantive action to slow Azerbaijan down, which also likely played into Baku’s thinking, Ahmadzada says. “If I were in [Armenia’s] shoes, I would not be expecting significant actions against Azerbaijan coming from the West,” he said.

Indeed, while the reaction from abroad to Azerbaijan’s September 19 attacks was swift and critical, it was limited to expressions of concern. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken called Aliyev to “urge Azerbaijan to cease military actions in Nagorno-Karabakh immediately.” The European Union said it “condemns the military escalation” and that the “violence needs to stop.”

“The international community is just making statements. It’s just statements,” said Edmon Marukian, an Armenian ambassador-at-large. “You know, statements are not helping when you’re attacked and somebody is trying to kill you.”

What Now?

The offensive managed to secure a concession that Azerbaijan has been demanding — and the ethnic Armenian Karabakh leadership has been fiercely resisting — for months: the disbanding and disarmament of the armed forces of the Karabakh authorities. Meetings between representatives of the Karabakh Armenians and of the central government in Baku are scheduled for September 21 in the Azerbaijani city of Yevlax.

A statement before that meeting from the de facto Karabakh presidency said that the talks would discuss the region’s possible “reintegration” into Azerbaijan and the Karabakh Armenians’ rights and security “within the framework of the Azerbaijani Constitution.” Those are conditions that Karabakh Armenians had previously considered unacceptable, but with Azerbaijan gaining the upper hand once again, their leaders had no choice but to accept them.

A week before the offensive, Armenian historian and diplomat Gerard Libaridian gave a lecture in the United States for his new book, A Precarious Armenia. He discussed the ongoing negotiations and argued that, as time goes on, Armenians’ bargaining position will become worse and worse.

“The more we wait, the less leverage we have…. Today, we cannot get what we could get last year. Last year, we couldn’t get what we could have gotten four or five years ago,” he said. “The more we have waited, the harder Aliyev has become.”