The case against the New Jersey senator has the potential to reshape how America deals with foreign agents.

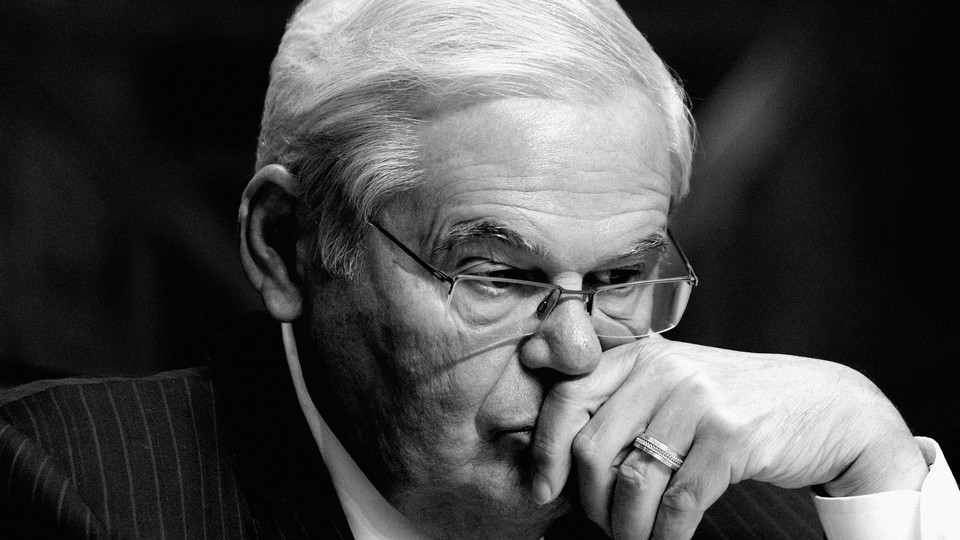

Stephanie Scarbrough / AP

Even before Bob Menendez was charged earlier this month with conspiring to act as a foreign agent, dozens of his fellow Democrats were calling on him to resign. Prosecutors say Menendez used his political office to influence American policy at the behest of the Egyptian government. He remains a senator—for now—but the latest indictment, coming after corruption charges last month, further complicates his fate. Last week, Menendez, who has pleaded not guilty to all counts, missed an all-senators classified hearing on Israel—no small indignity for a former chair of the Foreign Relations Committee.

According to the indictment, the senator from New Jersey passed along sensitive information to Egypt, acted as a ghostwriter for its officials, and accepted “hundreds of thousands of dollars of bribes.” While researching my next book, a history of the foreign-lobbying industry in the United States, I didn’t come across anything quite like these allegations. They appear to be the first time that an elected federal official has been formally accused of acting as an agent of a foreign government.

Menendez has repeatedly professed his innocence and his loyalty to America. After his arraignment earlier this week, he released a statement calling the foreign-agent charge “as outrageous as it is absurd.” His trial is set for May, when Menendez says he’ll be shown to have done nothing wrong.

Read: Why this time is different for Bob Menendez

Even if the allegations are disproved, however, they could reshape how America prosecutes and punishes the kind of misconduct that Menendez is charged with. Until recently, the U.S. has largely ignored its best tool for deterring covert foreign agents. The case against Menendez signals an overdue willingness to use it.

Menendez’s alleged behavior might be novel, but we were warned of its possibility centuries ago. The Founding Fathers recognized that, in some ways, America is particularly vulnerable to foreign influence. “One of the weak sides of republics, among their numerous advantages, is that they afford too easy an inlet to foreign corruption,” Alexander Hamilton wrote in The Federalist Papers. The danger may be greater today: Underpaid and overworked, U.S. officials are ripe for targeting by foreign powers eager to sway decisions in Washington. History, Hamilton noted, “furnishes us with so many mortifying examples of the prevalence of foreign corruption in republican governments.” Why would the U.S. be any different?

For years, these concerns appeared overblown. (Though not entirely: James Wilkinson, who served as the highest-ranking officer of the U.S. Army under each of the first four presidents, was revealed after his death to be an agent of the Spanish monarchy.) Then came the 19th century’s greatest foreign-corruption scandal.

In the late 1860s, Russia’s czarist regime was broke and desperate to sell Alaska, its easternmost province. So the Russian ambassador, Edouard de Stoeckl, secretly hired former U.S. Treasury Secretary Robert Walker to persuade Washington to buy it. Walker quickly obliged, publicly endorsing the purchase, planting articles in influential newspapers, and allegedly—no hard proof ever emerged—bribing legislators. Within a matter of months, Congress voted to back the purchase. When the details of Stoeckl’s gambit later spilled out, one critic described it as the “biggest lobby swindle ever put up in Washington.”

Walker’s offenses were shocking, but at least he had the decency to leave office before committing them. This sets him apart from the precedent that Menendez has now allegedly established. A more recent case, however, comes close.

In 1999, nearly 50 years after his death, Representative Samuel Dickstein of New York was revealed to have been a Soviet agent. KGB archives showed that Dickstein used his office to grant Soviets access to U.S. passports and, in one instance, to pass information about a Soviet defector who was later found dead in a hotel room.

Unlike other Americans recruited by the Soviet Union, Dickstein did not appear to have communist sympathies. Rather, Dickstein—whom Soviet officials nicknamed “Crook”—seemed interested only in money. “‘Crook’ is completely justifying his code name,” Soviet officials wrote. “This is an unscrupulous type, greedy for money … a very cunning swindler.” The Soviets eventually cut him loose, complaining that he wasn’t worth the price he demanded. Dickstein was never found out and spent the rest of his life in public office.

Read: How the Manafort indictment gave bite to a toothless law

The revelations were all the more surprising because Dickstein played an instrumental role in passing the Foreign Agents Registration Act, or FARA, America’s best safeguard against people like himself.

In the 1930s, he led a committee that found that Ivy Lee—sometimes called the “father of public relations,” whose clients included the Rockefellers, Woodrow Wilson, and Charles Schwab—covertly advised the Nazis, helping them launder their image in America. At one point, Lee encouraged Joseph Goebbels to cultivate foreign reporters; he told other Nazis to publicly insist that Hitler’s storm troopers were “not armed, not prepared for war.” (One unsigned memo I found in Lee’s archive described Hitler as “an industrious, honest and sincere hard-working individual.”)

Thanks to these and other revelations, Dickstein and the committee played a key role in persuading legislators to pass FARA in 1938, which required anyone representing foreign governments, especially lobbyists, to disclose what they were doing on behalf of their clients. Dickstein is the only known member of Congress to violate the law he helped enshrine.

According to prosecutors, Menendez largely followed Dickstein’s playbook—passing along sensitive information, steering American policy for the benefit of foreign patrons, and accepting staggering amounts of money for his efforts, including in the form of gold bars.

The fact that prosecutors employed FARA to charge Menendez is a welcome development. The legislation was underused for decades, as foreign-lobbying networks—including those targeting sitting officials—flourished. To cite one statistic: Only three FARA-related convictions were secured from 1966 to 2015.

That wasn’t for lack of rule-breaking. A decade ago, Azerbaijan’s dictatorship and its proxies recruited American lobbyists, scholars, nonprofits, and others to promote Azeri interests without disclosing any of their campaigns. Other dictatorships and budding autocracies followed suit. As one 1990 government report found, barely half of registered foreign agents disclosed all of their activities.

When Donald Trump emerged as a political force, FARA experienced something of a renaissance. Although the former president was never accused in court of acting as a foreign agent, some of his closest allies—including his campaign manager Paul Manafort and National Security Adviser Mike Flynn—were convicted on related charges. (Trump later pardoned them both.) But those prosecutions never targeted a sitting official. That honor belongs to Menendez alone.

The renewed interest in FARA has highlighted the ways in which the legislation can be improved. The legal definition of foreign lobbying needs clarifying, and the Department of Justice should be empowered to use civil fines (rather than just criminal penalties) to target covert networks. Effective reforms have been proposed, but they’ve stalled in Congress. As Bloomberg Law reported, one legislator in particular was responsible for thwarting them: Menendez.

If proven guilty, Menendez will come to represent the culmination of the Founders’ fears—perhaps the most “mortifying example” of foreign corruption in U.S. history. But whether or not he’s convicted, Congress could use the attention his case has drawn to strengthen FARA, keep foreign lobbying in check, and give would-be offenders more reason to fear concealing their activities. If the charges against Menendez are a black mark, they can be a turning point too.